Zouave regiments, uniforms and tactics of the American Civil War, 1861–1862

Since its inception in 1783, the United States had been a primarily agricultural society. Large sectors of the economy were based heavily in the raising, harvesting and sale of a number of crops to parties both within and outside the country. Cotton, tobacco and wheat were chief among them, with other more perishable crops relegated to commerce within the United States’ borders. The south provided perfect soil for the production of these crops, and slave labor provided a free workforce with which to work the land. With no wages to pay, the land owners would increase their profit margins considerably. This system, known to history as the Antebellum Era or Plantation Era, created a kind of land-owning aristocracy. Wealthy cotton farmers who either were directly in positions of political power or greatly influenced those who were.

The arrival of Abraham Lincoln on the political scene disrupted life considerably, with his anti-slavery rhetoric. Tensions between north and south escalated, with the Antebellum aristocrats claiming federal government meddling in their personal lives. Many in the north understood slavery to be immoral, both refused to back down from the positions. On April 12th, 1861, the states of Virginia, Texas, Tennessee, Arkansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida, Alabama, and Georgia seceded from the United States to form their own sovereign nation, under the principle of slave ownership; the Confederate States of America. Sections of Maryland and Kentucky would also join the rebels, their loyalty split between the two great powers. The war would eventually see units from the same state, fighting for opposing sides, facing each other in battle.

The Federal army was in little shape for a war on its own soil in early 1861. Uniforms had updated little since the Mexican-American War in the 1840′s, some units of the far-flung frontier hadn’t updated their uniforms since the War of 1812.

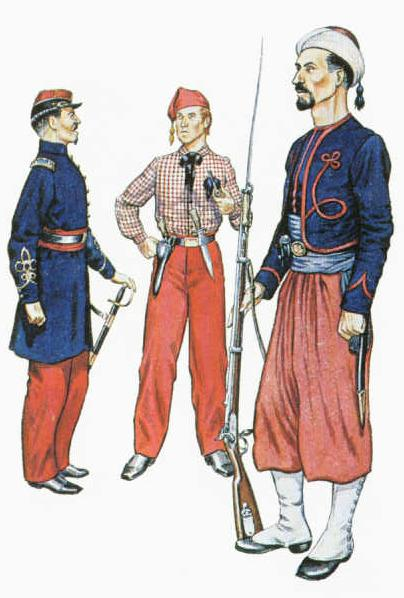

Uniforms were ironically non-uniform during this period. Each unit was responsible for providing their own outfits, with little regulation or oversight on what they looked like. Many regiments and battalions remained with the 1840′s pattern uniform as shown above. Many states did update their infantry uniforms, New York state reformed their standard uniforms to a steel grey color, which would largely be looted and then officially adopted by the rebels by 1863. The outbreak of war created new problems for the small US army, with Lincoln calling for 75,000 volunteers to oppose the alarmingly-expanding rebel army, vastly increasing the size of the United States’ standing force many times over.

However, as the United States had problems with uniforming their men, the rebel Confederate States had equal problems. A crippling lack of resources prevented them from providing uniform clothing to their men. Many rebel soldiers simply wore civilian clothing with military equipment over top. Looting from dead Federal soldiers became common, with more organized raids stealing large quantities of uniform components from depots at places like Harper’s Ferry.

From these newly created units on both sides, many of them adopted the flamboyant style of the French Zouaves. Red shirts, baggy trousers, fez caps and turbans became not uncommon on the battlefields of the early civil war. Some of these units included:

The 5th New York State Militia

14th New York State Militia “Red Legged Devils”

1st Louisiana Special Battalion, Co. B “Tiger Rifles” or “Wheat’s Tigers”

9th Louisiana Special Battalion

The outlandish uniforms were largely inspired by the French colonial infantry regiments of the same name. During the Second French Empire’s expansion into Algeria and Tunisia in the 1830′s, the French army encountered a wide variety of warrior peoples, primarily the warrior society of the Zwazwa. Fighting with a looser, more aggressive style than the French army had been used to, the Zwazwa took years to completely subjugate. During that time, the French public had grown endeared to them. Their particular style of clothing was adopted by colonial regiments stationed in Algeria, named the French pronunciation of the word. The Zouaves took the world by storm after that. Their uniforms became high fashion, their name and reputation was considered the last word in cool.

Many special companies took their unique brand of extravagance on tour across many countries, especially America. These tours would provide the inspiration to many local militia units across the nation to take up the uniforms, to better emulate the Zouaves.

In a way, Zouaves filled the same cultural role back in the 19th century as, say, cowboys would today. Roughened, maverick, loose cannons. Tough as nails. Hard drinkers. Womanizers.

At the outbreak of war in the United States in 1861, units on both sides adopted both the look and the style of fighting. On top of being more flamboyant, Zouaves filled an important role in an army’s make-up; irregular specialist troops. They fought in looser, reactive groups, rather than the rigid lines infantry regulars did. While smaller in numbers, they could pursue objectives other infantry types couldn’t. The Louisiana Tigers, for instance, found a niche as cannon-killers. Swinging around the lines to knock out cannon batteries, allowing the rest of their force to approach unopposed by artillery. Naturally, this was a very dangerous job. Batteries had special ammunition types for dealing with infantry, and would often have rear-line units not engaged in the fight standing guard. The 1st Louisiana was obliterated at the Battle of Gaines Mill in 1862.

Acting as light infantry, the Zouaves were also armed with lighter, smaller weapons. Most Zouave brigades and regiments were armed with carbine-style “two-band” muskets. Self-provided pistols were common place as well, with no regulations on armaments beyond the standard-issue rifle.

Often not issued bayonets, Zouave regiments would often arm themselves with bowie knives or machetes for close-combat roles. After-action reports from early battles of the war claim Zouave units firing off a single volley, then immediately closing the distance to finish off the opposing unit in a violent melee. Many Zouaves, especially those of Louisianan origin, on average had a criminal record of some variety. Mainly gangsters or dock workers, the men of the Tiger Rifles were more at home in a punch-up than a shootout.

As the civil war escalated, Zouaves became less and less of a staple unit as both federal and rebel armies became more adept at handling situations. As American use of Zouave infantry died out, French use remained. The infantry type would remain in use within the French army all throughout the First World War and Second World War, only dying out after the Indochina War in the 1960′s. While the Zouaves of the 20th century retained their role as specialist colonial units, their uniforms changed to more conventional greens and browns, to better suit the surroundings in which they fought.

In conclusion, the Zouaves served many roles to many people, some becoming contradicting as they crossed cultural lines. From flashy showcases to front-line troopers. From elite soldiers to former criminals. But no matter where they went, they all shared one thread of commonality; Zouaves were always spoiling for a fight with whoever wanted one.

Jones, Michael D. Making of a Louisiana Legend. New Orleans: Self-published, 2011. Print.